TSANG TSOU-CHOI

THE KING OF KOWLOON

Available in French on ACA (Asian Contemporary Art) Project’s website here

Written 10th July 2023, by Amandine Vabre Chau

Looking back on the King of Kowloon

A King in the Making

Known as the "King of Kowloon", this Hong Kong figure was -and still is- conflicting for many people. Born in 1921, Tsang Tsou-Choi was a garbage collector turned artist against his will. Currently exhibited at M+ Hong Kong, he earned his title by baptising himself the rightful king of the Hong Kong Kowloon peninsula.

The story goes like this: Tsang is the rightful king of Kowloon as the territory was given to one of his ancestors by a Chinese Emperor. At first only referring to the peninsula, he soon considered the entirety of Hong Kong his. No one knows for sure how he came to believe so and there has been varying reports of his obsession's origin. One of these states that he found family documents testifying his ancestral clan’s ownership over the territory. Another, more common, says it was due to an accident which rendered him disabled and led to mental health issues. His family stayed out of the spotlight and officials never recognised his claims. None of this stopped our protagonist from becoming a Hong Kong cultural icon, even leading to his inclusion at the 2003 Venice Biennale, before his passing in 2007.

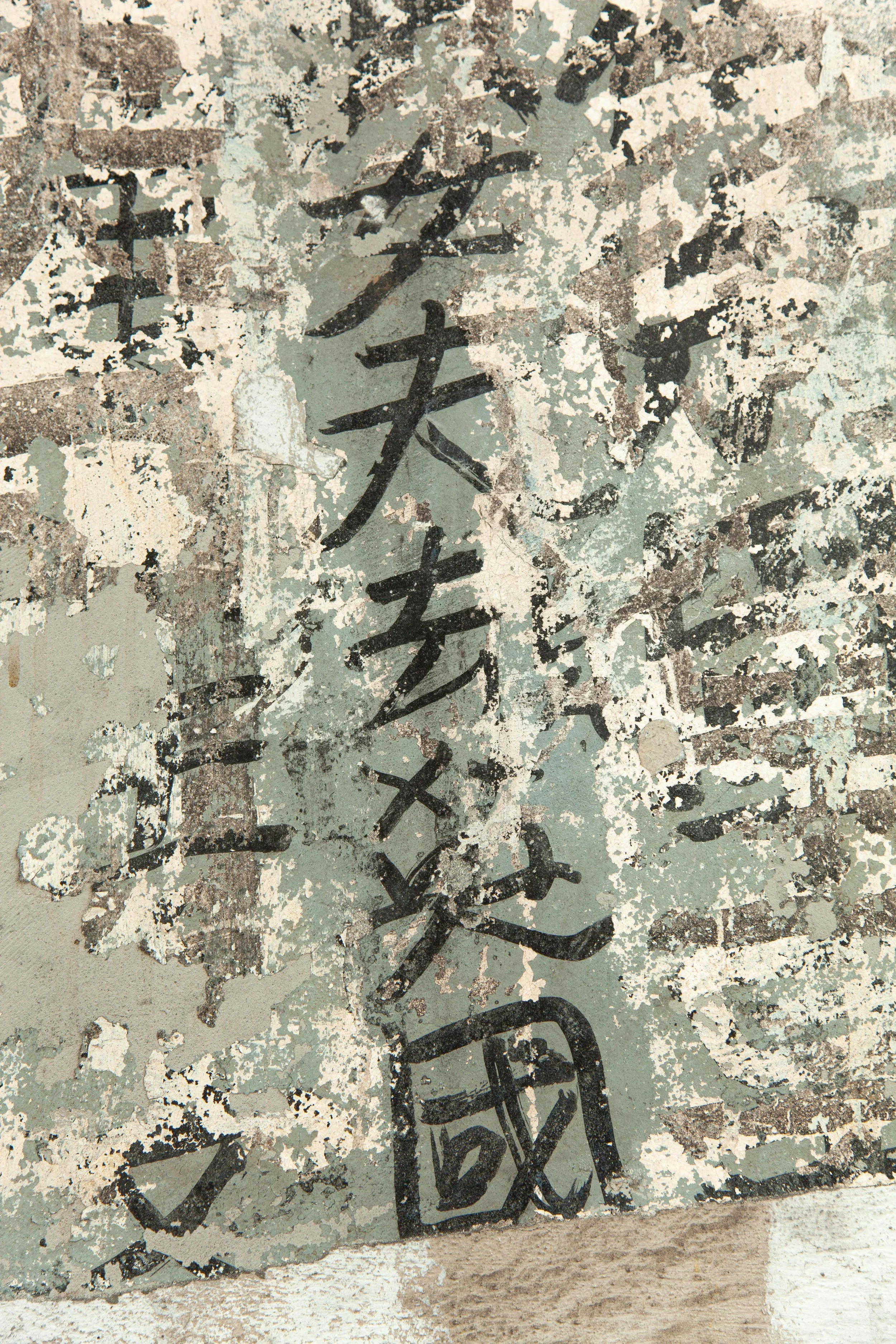

Peeling paint reveals Tsang Tsou-Choi (King of Kowloon) intervention at Boundary Street, Hong Kong – © Amandine Vabre Chau

An unexpected tale of defiance

He began his campaign at 35 years old, starting as all good Kings do when land is stolen from them: by declaring war. Calligraphy was Tsang’s weapon of choice and the city was his canvas. In the mid-50s, armed with a wolf-hair brush, he began writing in public spaces. Mostly walls, pillars, electricity boxes, lampposts and various government-owned structures. Indeed, he picked carefully by only targeting crown land (when Hong Kong was a British Colony) then government land (when it returned to China in 1997). At first, neither the Authorities nor the public considered his work art, instead calling it vandalism or 'ink writing' at best.

Having attended school for only two years, his Chinese characters were irregular and occasionally incorrect but never hesitant. Instead, they were imposing, big, visible, and absolutely impossible to ignore. With an estimated 55 845 works in public spaces, he managed to build a city in his own image. Bearing witness to his endeavours, his subjects saw him play a masterful game of graphic hide and seek with the government. Each time one of his new creations was painted over by government cleaners, he would come back to cover the entire surface again. Tsang Tsou-Choi was unyielding when confronted with the erasure of his work. Determined to be heard and have the world witness his loss, he would write all 21 generations of his lineage to explicit who the government stole from. Adding his name, numbers, significant dates along with insults such as “Fuck the Queen”, he would also ask people to refer to him as “Your Majesty” and occasionally ask the ruling powers -which he called imposters- to pay him land taxes.

Hong Kongers began to slowly but surely take a liking to the King. If not for his debatable talent, at least for his sheer audacity. A comical tale at times, an awe inspiring one at others. A man, bold and reckless, somehow decided to challenge two global superpowers every day for the rest of his life. Furthermore, he did so without being discreet and chose an unconventional eruption of childlike provocation. It appeared as if he was an organic byproduct of the larger socio-political issues in Hong Kong, resulting from a mounting tension felt by many. The most unlikely of icons, a product of the absurdity of his time. Instead of artist or fool, he chose the title of King.

Tsang Tsou-Choi (King of Kowloon) preserved work on lamppost, Pink Shek Estate, Hong Kong © Amandine Vabre Chau

TsangTsou-Choi (King of Kowloon), preserved work on pillar, Tsim Sha Tsui Pier, Hong Kong – © Amandine Vabre Chau

Political context and social background

Hong Kong was passed on from China to Britain and back to China again under a coerced agreement signed by both parties where the inhabitants of Hong Kong were not consulted. Britain, hungry for tea and porcelain, required China to cede part of its territory for trade unless they were to face invasion. When the metropolis was returned to China in 1997, as the former agreement stated, the ruling powers agreed on the “One Country, Two System” principle. A constitutional principle declaring that Hong Kong was to remain unchanged for 50 years, continuing with its own laws and system developed under the British empire, until 2047 when it will be returned to China in full. This effectively activated a countdown until the end of this purgatory. To simplify the divide in 1997: on one hand some had colonial nostalgia for a supposedly better ruler that introduced a way of life with capitalistic characteristics; on the other were patriots who remembered very clearly the century long humiliation China endured at the hands of European colonisers. Then, some refused the either/or logic and identified with a growing local culture. With this context, the significance of Tsang Tsou-Choi takes on another meaning. Even if unconsciously, he managed to slip between the cracks of the system and embody a growing sense of discomfort.

Remaining traces of Tsang Tsou-Choi’s (King of Kowloon) intervention on Queen’s Road Central, Central, Hong Kong – © Amandine Vabre Chau

Artistic practice and its symbolism

Our conception of art is reevaluated every now and then, as it should. If our interpretation was to remain unchanged, the art world would regress. Art is bound to change, transform and adapt to its times. That is why Tsang’s calligraphy came to be an important part of Hong Kong visual culture. It emerged at a specific time with a specific approach in echo to his larger environment. His work was visually bold and bizarre. It did not conform to traditional calligraphy standards, too imprecise in its execution. Yet the accumulation of his thick characters, stacked on top of one other and forming an ensemble of strange cubic writing, invaded every surface with an impossible urge. A surprising quality coupled with a calculated choice in his medium. Indeed, calligraphy was an Emperor’s art, and Tsang continue this tradition by reappropriating it. He was careful to place his characters from top to bottom and from right to left, making sure his pieces were read in the Chinese traditional way. He calculated the size of his words, enlarging certain characters to take up the space of 5, drawing your attention to it. This character, almost always read “King”. Placing his signature front and center, you were to witness his visual takeover.

Unfortunately, out of the 55 845 works, only three survived in public spaces. A few were transported to museums along with some objects he painted on after people asked him to. In his final years, more and more people got interested in his work. As walls are difficultly removed to sell, some gave him bottles, tee-shirts, and other items to write on. More and more fashion designers, art directors, interior decorators and curators met with him. His calligraphy was soon found on various commodities and he was even featured in movies and commercials. Rightfully so, the public expressed ethical concerns about bringing a person with mental health issues into an unscrupulous commercial ecosystem. We could also question the relevance of having him write on these objects when his purpose was to demonstrate his dominion over stolen land with massive public works. More significantly, there was the fact that Tsang never considered himself an artist. He had clarified his stance on numerous occasions, maintaining his status as a wronged King. After all, isn't it questionable to turn a living person into a symbol they have never claimed?

Still, Tsang-Tsou Choi spoke to people by being an ordinary man who achieved the extraordinary. With his flaws and peculiarity, against all odds and even against his will, he offered a glimpse of what irrationality could accomplish, and was engraved into our collective memory for doing so.

Peeling paint reveals Tsang Tsou-Choi (King of Kowloon) intervention at Boundary Street, Hong Kong [detail]

– © Amandine Vabre Chau

Peeling paint reveals Tsang Tsou-Choi (King of Kowloon) intervention at Boundary Street, Hong Kong [detail]

– © Amandine Vabre Chau

Written 10th July 2023, by Amandine Vabre Chau

![Peeling paint reveals Tsang Tsou-Choi (King of Kowloon) intervention at Boundary Street, Hong Kong [detail] – © Amandine Vabre Chau](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/640dcc1d9a63e5441c65f230/aa1259fa-e537-4eb0-8c19-ff8d2f614a22/Peeling+paint+reveals+Tsang+Tsou-Choi+%28King+of+Kowloon%29+intervention+at+Boundary+Street%2C+Hong+Kong+%5Bdetail%5D+%E2%80%93+%C2%A9+Amandine+Vabre+Chau)